Investor Psychology & Market Rationality Argument

KIRAN KUMAR K V

Market Rationality Argument

There are certain suppositions upon which markets work. It assumes that human beings are rational, in fact, always rational. Their sole objective is to maximize the return for a given level of risk that they are taking. The concept of risk-adjusted return, that’s the foundation block of many asset pricing and valuation models, highlights the risk-aversion behaviour of investors. Risk-aversion relates to the behaviour of individuals under uncertainty. If an individual is offered two options: one, where he will get Rs. 50 for sure and two, a gamble with a 50% chance of getting Rs. 100 and another 50% chance of getting nothing. The investor may react in three ways: He may choose the latter and gamble; He may choose the former and be conservative; He may choose to be indifferent, as the expected value before the bet in both the cases is Rs. 50

When he chooses to gamble, he is referred to as risk-seeker. A risk-seeking or risk-loving investor chooses uncertainty over certainty, as he gets extra ‘utility’ from the uncertainty associated with the gamble. It can be observed in individual’s behaviors like buying a lottery, or gambling in a casino or even sitting on a giant wheel. Risk-seekers are also the ones who calculate the risk. Let’s consider in the above example, if the latter option gave a 40% chance of getting Rs. 50 and 60% of nothing, a risk-seeker may have avoided the gamble.

When he chooses to be indifferent, the investor is referred to as risk-neutral. He is an investor who cares only about the return. Uncertainty is not at all a parameter of analysis for a risk-neutral investor. A risk-neutral behaviour can be found when the investment at stake is insignificant part of their wealth.

If an investor chooses the guaranteed income over gamble, he can be referred to as a risk-averse investor. He will generally shy away from risky investments, even if the return is lower as long as it is guaranteed. That does not mean he will not at all take risk. It just means that he is not comfortable with the return he is getting for the amount of risk he is assuming. He looks for a risk-return tradeoff that results in that extra-utility for him. Because individuals are different in their preferences, all risk-averse individuals may not rank investment alternatives in the same manner. Take the example of Rs. 50 gamble; all risk-averse individuals will rank the guaranteed outcome of Rs. 50 higher the option of gambling the same. What would have happened if the guaranteed outcome was Rs. 40 and not Rs. 50? Some risk-averse investors might consider Rs. 40 inadequate, others might accept it, and still others might become indifferent. This suggests that individuals are risk-averse and they prefer more to less. They are also able to rank different investment alternatives in order of their preference and such ranking are internally consistent. Such utility function is represented by the economist’s function: &

nbsp;

nbsp;

Where, U is the utility function, E(r) is the expected return and is the variance of the investment and A is the measure of risk-aversion. It can be computed as the marginal reward that an investor requires to accept a unit of additional risk. A higher risk-averse investor requires greater compensation for accepting additional risk (a higher A) and vice versa.

Apparent Irrationality

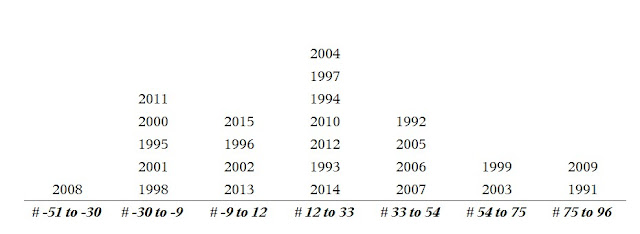

Figure 1: Sensex Returns 1991-2015 (Source: Author’s Calculation) |

The non-normal distributions of returns of Indian stocks in the past 25 years or so show that there is a positive skewness. That also means there is higher frequency of positive deviations from the mean. If the investors were rational and always took the right decisions in terms of computing their risk-adjusted returns, the distribution of returns must have been normal (assuming the central limit theorem could be applied here, as Sensex in itself a portfolio of 30 companies and we are attempting to present returns for 25 years). The only conclusion we can draw is that there is an anomaly here that is either underestimating or overestimating the risk (as measured by the standard deviation) by the investing community.

Investor Psychology as an Explanation

While the major blocks of investment finance, like the mean-variance portfolio, CAPM, investor rat

ionality and risk-return trade-off have been the ingredients in valuation and security analysis models widely used in real world, there is also an argumentative perspective to the (above-discussed) basic tenet upon which such models are constructed. Behavioural Finance questions the very assumption that people are guided by reason and logic and independent judgment. It is also possible that investors are not rational, at least always, and emotions and herd instincts might be playing a role in influencing their investment decisions. This approach attempts to enumerate explanations why individuals make the decisions they do, irrespective of rationality. Few such behavioural inconsistencies are discussed below to give an idea of the approach:

ionality and risk-return trade-off have been the ingredients in valuation and security analysis models widely used in real world, there is also an argumentative perspective to the (above-discussed) basic tenet upon which such models are constructed. Behavioural Finance questions the very assumption that people are guided by reason and logic and independent judgment. It is also possible that investors are not rational, at least always, and emotions and herd instincts might be playing a role in influencing their investment decisions. This approach attempts to enumerate explanations why individuals make the decisions they do, irrespective of rationality. Few such behavioural inconsistencies are discussed below to give an idea of the approach:

– Representativeness Bias: A tendency to form judgments based on stereotypes. An investor may see the effect of a policy rate change by the central bank based on historical trend

– Anchoring Bias: A tendency to be unwilling to change an earlier decision, despite a new, relevant information arrival

– Familiarity Bias: A tendency to be comfortable with things that are familiar to them. Being familiar with employer or the industry they work in people tend to invest in the known sectors.

– Affect Heuristic Bias: A tendency to go by the gut feel or intuition.

– Innumeracy Bias: A tendency to give more focus on big numbers and less weight to small figures. Ignoring the base rate, wrongly counting the probability of an event

– Loss Aversion Bias: A tendency of people to dislike losses more than they like comparable gains. Many overreactions or panic selling in market we have witnessed occur due to this bias. Especially, in countries like India, where generally the retail investors are largely conservative in their risk appetite, we see an increased overreaction

– Narrow framing Bias: A tendency of investors to focus on issues/events/portfolios in isolation and respond based on hos such issues are posed

– Mental Accounting Bias: A tendency of investors to keep track of gains and losses for different investments in separate mental accounts and treat those accounts differently

– Shadow of the Past Bias: A tendency of people to consider a past outcome as a factor in evaluating a current risky decision. A Snake-bite effect refers to the behaviour where individuals being less inclined to take risk after a incurring a loss.

– Herd Instinct Bias: A tendency to move with the group, even if one has a contradicting solution

The biases discussed above are just a few examples of what behavioural finance approach assumes to be the reasons for markets being inefficient (i.e., market prices always uncorrelated with any known variable). Behavioural finance thus can be seen as a contrasting approach to the traditional investment finance theory and the market efficiency theory. Behavioural finance seems to have answers for irrationality of market prices in converging with the intrinsic value.

Behavioural biases affect all market participants. Now the question is how do rebuild the asset pricing or valuation models to account for behavioural biases such that all the factors – rational & irrational (behavioral) – that influence the price discovery in security markets are accounted for and fully reflect the causations of given market behaviour. If there can be a model that can do this, market participants would be able to recognize, respond and make improved decisions, individually and collectively.

References: Behaviour Finance, Chandra, 2016; Investopedia; IAPM, Reilly & Brown, 2014